Almost-art has some of the same properties of art, but not all. Almost-art has many of the same properties of non-art, but it has something extra that sets it apart. With the comments below I attempt to show how the concept of almost-art fits in with other aspects of aesthetics, and life in general.

Aspects of Art and Almost-Art

The Art-Object

If we consider Nature as an actor and as an artist, then perhaps we could consider everything to be art. But the very essence of art is that the art-object is distinct from Nature. I've seen an exhibit outside a popular restaurant that was nothing but a garbage can with fake garbage in it and around it, and the whole thing was under Plexiglass with the artists name on the identifying plaque. This was obviously made to impress on the observer that anything in the world that we happen to find could be set apart and identified as art. This act of "identifying" is a key ingredient to the artistic experience. In 1917, French conceptualist Marcel Duchamp famously placed a urinal in a New York gallery and declared "this is art." This urinal was an example of what he termed "readymades," or things that could be identified as art without the identifying "artist" adding anything to them. Another one of his "readymades" was a bicycle wheel mounted on a wooden kitchen stool. It is generally accepted that the deliberate identifying action is necessary, even if it is just a mental and transitory personal one.

Not to detract from the importance of Duchamp's "readymade" idea, but usually we expect that the artist actually contributed to what is then considered to be the art-object. In his Reason in Art, Volume IV of The Life of Reason, George Santayana described art as the remodeling of nature by reason. This can sometimes put us in the odd position of declaring that Less is More: that is, that a quick two-dimensional drawing of a mountain by a poor artist is more "art" (is more artistically rendered, or embodies the "art" ideal more) than the real mountain. Likewise, we would have to say that a photograph of an artist is more "art" than the artist (who can take many photographs). Making this distinction—between what is "natural," and what is "nature remodeled by reason"—creates the possibility that the artist, over the years, can contribute to him or her self as a work of art (consider the finessed look of Salvador Dali, or the acting ability of Jim Carey, for example).

So we must be very careful with our wording. For any discussion on art one needs to clearly distinguish between the following three things: art-object, artist, and observer. Considering the above example, we would then say that Jim Carey was both artist and art-object. The man is, literally, a work of art. (And perhaps we all are, or aspire to be, a "work of art;" and we would thereby acknowledge that there can be great deal of artistry to parenting, and teaching, and learning.)

Another distinction that accompanies any discussion on art is that between mental (thoughts, feelings, ideas), and physical (objects, nerves, sound waves in air, etc.). The physical art-object mediates between artist and observer. That is to say, at some point in the artistic process, the art-object takes on the function of language: as an idea is first encapsulated, and then abstracted through understanding (as is the function of language in general).

Art and the Senses

Humans have a certain ability to senses things. For example, we have the senses of touch, taste, smell, hearing, and sight. In all of these senses we have a limited range. We can't hear the same frequencies of sound as dogs, bats, or elephants; and we can't see ultra-violet or infra-red light. We can't smell like dogs, or taste like cats. We can't sense the Earth's magnetic fields in the same way that some birds and sea animals can. We need special devices to enable us to detect radio and television signals, and we still need a lot of help detecting neutrinos, or dark matter.

In other words, the odds are exceedingly low that if we met ET our senses would be aligned correspondingly, and so well that we could communicate without problems and appreciate each other's art. So, for the purposes of this analysis, we are considering Earth-bound and human art, and leave this wider discussion for some other time.

| Sense | Its Contribution ot the Flow of Artistic Ideas | Degree of Artistic Contribution (or Complexity) |

|---|---|---|

| Touch | The sense of touch aids in the appreciation of sculpture and form. | Low |

| Taste | The sense of taste aids in the appreciation of the culinary and mixological arts. | Low |

| Smell | The sense of smell aids in the appreciation of the culinary, and the olfactory and perfume arts. | Low |

| Hearing | The ability to detect minute fluctuation in air pressure helps in our appreciation of the musical arts, the dramatic arts, and the linguistic arts. | High |

| Sight | The ability to see aids in our appreciation of drama, dance, literature, painting, drawing, architecture, sculpture, computer graphics, photography, movies, hair styling, and fashion. | High |

It is often or generally accepted that what we classify as art needs to inspire the mind in more than just base ways, and so that which only caters to the senses of touch, taste, and smell are relegated almost entirely to what we are calling here "almost-art" and "non-art." Likewise, most of what falls under the general groupings of hair styling, clothes fashion, most photography, most architecture, and disco music, may or may not be considered "high art," "fine art," or even fully "art."

The Beginning of Art

In that art must inspire thought, it must be symbolic. In his Lectures on Aesthetics, G. W. F. Hegel said that symbolism was "the beginning of art." He said, "We must then distinguish the symbol, properly speaking, as furnishing the type of all the conceptions or representations of art at this epoch, from that species of symbol which, on its own account, is nothing more than a mere unsubstantial, outward form." (Here he is, like Santayana above, distinguishing between what is natural from what is created.) (Note also, here, that with the inclusion of the word "epoch" he recognizes the time dimension in artistic considerations.) I would add that all of what we know to be "art" is part of an "emergent evolution," and that our universe continues to sprout new emergent properties, and once extant they may be used and viewed aesthetically.

Art predates history in that it originated with drawings in sand, decorated pottery, painted faces, jewelry, and cave paintings. Art emerged through almost-art. The symbolism and communication aspects were always present. Ernst Haeckel's famous phrase in biology "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny" can easily be reapplied to the development of art in individuals and civilizations: we start with the fundamentals and work our way into sophistication and mastery.

Oscar Wilde later added (from the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray), "All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril." The identification and the symbolic aspects are what are essential to all further considerations of art.

Art as Impure Concept

As the above quote from Oscar Wilde warns, there is no such thing as pure art (that is, something that is nothing-but-art). When we observe an art-object at the molecular level, we have moved into the realm of chemistry, and are looking at Nature rather than art. When we throw a small sculpture at someone, it becomes a projectile and a tool, as remains an art-object only until it breaks.

Nelson Goodman, in his Ways of Worldmaking, said: "To say what art does is not to say what art is; but I submit that the former is the matter of primary and peculiar concern. The further question of defining stable property in terms of ephemeral function—the what in terms of the when—is not confined to the arts but is quite general, and is the same for defining chairs as for defining objects of art. The parade of instant and inadequate answers is also much the same: that whether an object is art—or a chair—depends upon intent or upon whether it sometimes or usually or always or exclusively functions as such." He then goes on to say: "I have turned my attention from what art is to what art does." He adds, "A salient feature of symbolization, I have urged, is that it may come and go. An object may symbolize different things at different times, and nothing at other times." [The bold emphasis above is mine.] So, just because a chair is sold as something to sit on, that does not mean that it can't be beautifully rendered, or serve as a stepladder, or boat anchor, or home for termites.

From A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce describes what he calls "Improper Art." He said: "The feeling excited by improper art are kinetic, desire or loathing. Desire urges us to possess, to go to something; loathing urges us to abandon, to go from something. These are kinetic emotions. The arts which excite them, pornographical or didactic, are therefore improper arts. The esthetic emotion (I use the general term) is therefore static. The mind is arrested and raised above desire and loathing." Therefore, for the purposes here, I would include art used in advertising, pornography, or education as being almost-art for this reason alone: that its use has sufficiently polluted the perception of the art-object that it can't (again, only in the particular usage, the "when") be fully art. (That doesn't stop me from going to an advertising film festival every once in a while.) We notice Goodman's and Joyce's distinctions when society admits the depiction of a woman's breast on the cover of National Geographic, or in and art gallery, but disparages the depiction of a woman's breast on the cover of Playboy, or on television during prime time. We seem to be remarkably aware, both consciously and subconsciously, of the uses and possible uses of things generally, and of the particular suggestions being made to us by presenters.

The above descriptions describe the zoom, the temporal, and the situational aspects of art. Seeming to agreeing with the above sentiments, Oscar Wilde put it this way: "We can forgive a man for making a useful thing as long as he does not admire it. The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely. All art is quite useless."

We have terms like "serious art," "high art," or "fine art" that are often reserved to denote "art for art's sake." The term "fine art" was coined in 1767 (originally in French as "beaux-arts") in reference to the arts that were "concerned with beauty or which appealed to taste." The list of traditional "fine arts" include: painting, sculpture, architecture, dance, opera, theater, poetry, and music, but there is no particular reason why other forms are not embraced under this umbrella (for example: movies, or the computer arts, might now rightfully be in the pantheon of arts). The number of fine arts need not stay fixed: for example, before computers, there could not have been computer art, so that is new (computers and computing being emergent aspects of our universe); and the art of whittling has all but disappeared (its social niche has all but disappeared in many counties). Also, and often, the boundaries between forms are blurred.

Why Almost-Art is a Useful Concept: The Various Artistic Scales

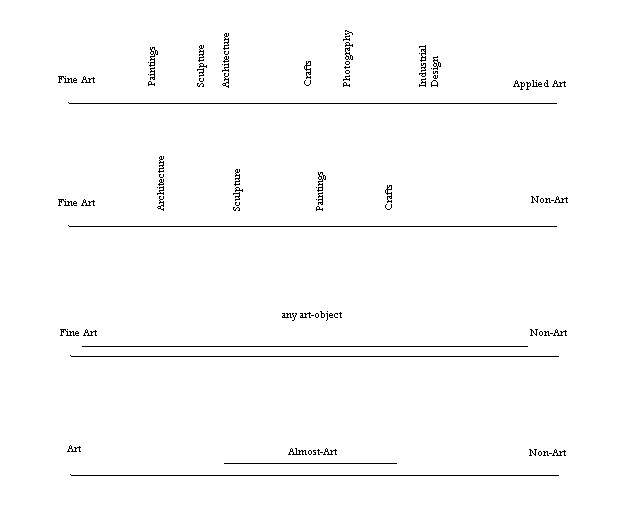

The following chart includes various conceptions of how things fit into the art world. The first line might describe the way we think of the art world today. The second line might describe the way people saw the art world in ancient times. The third line describes the art world before the introduction of almost-art, where any art-object fits somewhere on the sliding scale between "the most artistic thing in the universe" and "not very artistic at all" (here allowing subjectivity full reign). The fourth line describes the art world after the introduction of almost-art as a "grab-bag" category referring to things that "don't quite measure up" as art because of one or more of the Reasons presented on the Reasons page.

The important thing to glean from the considerations presented in this chart, and in what I'm saying here about almost-art, is that just about everything about art is on a scale (actually, many scales simultaneously) and is more or less (higher or lower) than something else on the scale(s) both as considered by objective criteria, as well as considered by more culturally-determined and subjective criteria.

The Social Connection

Art is never only surface. Art is not only in the paint, or the surface of the sculpture; not only in the note being played, or the word said. Art is something that comes to us not only from the front (from the work) but also from the side (society, and culture), and from behind (from history, and our prior learning). Art can't exist in a social vacuum, but, rather, it is a form of communication. Benbow Ritchie, in his article "The Formal Structure of the Aesthetic Object," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, describes a formal value as that interest which is "aroused by some aspect of the aesthetic object," and an extra-formal value as that interest which is "brought ready-made to the object." He describes two ways in which we appreciate Shakespeare's Julius Caesar: first, we bring our interest in politics and history with us (hence the appreciation of the work involves extra-formal value); and second, we appreciate the craft intrinsic to the work (for example: Anthony's funeral oration, the formal value). (See distinctions AAR-3, AAR-5, AAR-6 and AAR-8, on the Reasons page and chart.)

The Importance of the Signified

In his Critique of of Pure Reason, Immanuel Kant identifies concepts and ideas, when they are being communicated and understood, to be different from mere sensations, perceptions, and representations, and it is this kind of distinctions that is common among many descriptions relating to the nature of art.

In the Course in General Linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure described a sign as having two parts (his version of "the sign" being referred to as dyadic): the signifier, and the signified. From this we can then relate the sign and the representation and say that the art-object is the signifier, and anything beyond our mere perception and sensation would be the signified (of the art-object)—which would include the extra-formal value, and which could include any knowledge we glean, the intuition we have about it, a concept (either empirical or pure) that we may start interpreting and understanding by way of notions and ideas and concepts of reason.

There are two main approaches that are alternately favored by artists: First, an artist can try to express an idea: that is, he or she already knows exactly what to communicate and in what way. The second approach is that of experimentation, through mastery of the medium. Perhaps the first of these approaches has more consistently led directly to the production of something of import within the art world, but not always (some of our greatest works have been described as accidents of experimentation by the artist). The point being that the more the art-object is seen as expressing more than just something "surface," the more elevated we typically consider it to be on our scales of artfulness.

The Signified Within the Semantic Space (of the Society)

One way of seeing an idea is that it is "open-end encapsulated." That is to say, an idea is both open and closed to the rest of its semantic space. In his book Art As Experience, John Dewey says: "The main reason that ordinary experience is so rarely perceived aesthetically is that it is generally shot through with stereotypes. Recognition, as Mr. Dewey puts it, takes the place of aesthetic perception.

Another but similar way of seeing an idea is that it is comprised only of other ideas, and those other ideas are comprised only of other ideas, and so on, off into the semantic space, . . . without end. That is why we give words definitions. Therefore, we can safely and uambiguously consider ships to be big, for example, without confusing the meaning of the two words "ship" and "big." Words have a place within a dictionary, and ideas have a place within a semantic space. Jacque Derrida describes his concept of the "trace" as being that part of the sign that is not present. The sign and the supporting semantics cannot be divorced. An art-object can't be separated from what it is saying. What we see in any work of art stops when we as observer apply the "brakes of parsimony" ourselves.

The History of Art

Over time, art changes: from everyone wiggling their paint brush one way, to everyone wiggling their paint brush a different way. This is not a deep subject. The history of art is really, and merely, the history of the human use of symbolism, and is best considered in that context. What you have left is a collection of artifacts, each to be considered on their own merit.

The Importance of Logical Relativism

If the understanding of art were entirely subjective, then no two people would agree with respect to aesthetics, and the "artist" would therefore not be able to communicate artistically in non-random ways. There would be no common artistic ground, and therefore no real art. On the other hand, if aesthetics were an objective and absolute thing, there would be no question about it, we could quickly determine what would be the most artistic version of x, make that, and be done with the whole enterprise. In his 1946 article "Relativism Again," in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Bernard Heyl says: "A pernicious and prevalent idea claims that there are only two possible critical positions toward evaluation. Accordingly we must either be subjectivists or objectivists, nihilists or absolutists. No middle ground is possible. . . . I hope to show that a third position, relativism, is one that presents basic differences from both subjectivism and absolutism . . . and should thus eliminate the alleged necessity for accepting either of the two unsound alternatives."

Relativism has been criticized, but mostly for its sounding like subjectivism: that what is good depends on what you happen to like, and one thing is as good as another. It is sometimes neither agreeable nor particularly artistic to try and keep up with ever-changing values in art. Heyl says: "Like Subjectivism, that is to say, one aspect of relativism holds that value exists, not ontologically, but psychologically—as, for example, 'the qualitative content of an apprehending process.'" He agrees with John Dewey in contrasting subjectivism and relativism this way: considering their differences (respectively) as: requiring taste, or also judgment; the difference between the desired and the desirable; the satisfying, and the satisfactory; the admired, and the admirable. In this way we extend beyond just what we ourselves think when it comes to the relativistic view, and we are in time and still thinking, not appealing to elusive absolute ideals. Heyl says: "By elucidating his standards the critic enables his audience at least to understand his evaluations. This principle, which I call 'Logical Relativism,' is perhaps the most stabilizing one in criticism."

According to Logical Relativism, you can state what you put a premium on: technical perfection, the beauty or appeal of the work, the physical size of the work, the importance of the communication, the degree to which it is controversial, etc. For example, we might say that the computer game that is fun to interact with is better than the one that is bug-riddled, the painting that keeps us entranced is better than one we consider unworthy of our gaze. In doing so we apply personal values, values that we share with those around us, and values we consider to be objective (if not absolute, like scientific measures). A relativistic view allows one to have atypical, divergent, and even opposing standards, which differs from the absolutist view which would insist that seemingly contradictory values be resolved, and winners declared.

Art and Nature

While art is usually considered to be categorically distinct from Nature, it is also very much a part of the universe we live in, and therefore of Nature. The distinction is therefore as artificial as artifice itself. One need only point to Katherine Lee Bates' America the Beautiful, the Beatles' Mother Nature's Son, or John Denver's Rocky Mountain High to see syntheses of what is natural and what is art. Again, when John Denver teamed up with Jacques Cousteau for the undersea exposé featuring the song Calypso, we again marveled at how the two complemented each other in unity.

Who Cares About All This

In his book The Painted Word, Tom Wolfe said, ". . . if it were possible to make such a diagram of the art world, we would see that it is made up of (in addition to the artists) about 750 culturati in Rome, 500 in Milan, 1,750 in Paris, 1,250 in London, 2,000 in Berlin, Munich, and Dusseldorf, 3,000 in New York, and perhaps 1,000 scattered about the rest of the known world. That is the art world, approximately 10,000 souls—a mere hamlet!" (His book was published in 1975, but you get the idea.)

When we consider aesthetics more generally though, everyone cares at least a little bit, and often. We might care about vastly different things, and in different ways, but to most people their artistry defines them. We are proud of the art within us. We all want to do "a quality job" where it counts. No one wants to leave the house with something stuck between their teeth. We all want to express ourselves, and when we do we want to be appreciated. (Even nihilists speak in complete sentences.) It would be extremely difficult to find anyone who did not care about some art form, and most can proudly point at something artful they have done. So in this sense: Who doesn't care?

Art appreciation happens to be a common psychological trait amongst people if only in that it is so much a part of survival, understanding, expression, and reason.